Imagine you’re cooking a new recipe. You read the first step: “Chop onions.” So, you hop on your bike, ride to the store, and buy onions. Back home, you chop them and move to the next step: “Add tomatoes.” Off you go to the store again to get tomatoes. I mean sure, who hasn't had to run to the store for a missing ingredient or two? But who in their right mind would shop for ingredients one at a time in middle of cooking!?

In the real world, this approach would be wildly inefficient. But in the world of programming, there are situations where this step-by-step “just-in-time” behavior called lazy evaluation is exactly what you need.

Instead of buying everything upfront, lazy evaluation waits. It doesn’t “shop” for a value until you specifically need it. It’s like having a personal shopper who stands by, ready to grab the next item on your list only when you’re ready for it. This saves time, avoids waste, and keeps your workspace (and memory) clean.

So, What Exactly is Lazy Evaluation?

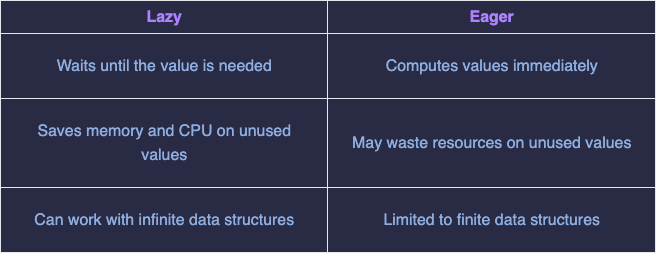

Lazy evaluation is a programming strategy in which computations are postponed until their results are explicitly required. Unlike eager evaluation, where every expression or operation is immediately calculated as soon as it is encountered, lazy evaluation defers the work until it becomes absolutely necessary. This means that instead of calculating everything upfront, regardless of whether the results will actually be used, lazy evaluation waits patiently, holding off on computation until the program demands the value.

This approach allows programs to operate more efficiently by avoiding unnecessary work. If a value is never needed, it is never computed, saving both time and resources like CPU cycles and memory. At its core, lazy evaluation transforms computations into placeholders or thunks—functions that encapsulate the delayed work, so the program can evaluate them only when needed.

Lazy evaluation shines in situations where:

- You’re working with large datasets and want to avoid wasteful computations.

- You’re handling infinite sequences that can’t be processed upfront.

- You need efficient memory usage without overloading resources.

This “just-in-time” approach is particularly useful for working with large datasets or infinite sequences, where computing everything upfront would be impractical or impossible. By deferring work until the last possible moment, lazy evaluation ensures that computations are as efficient and resource-friendly as possible. It is a strategy that prioritizes doing less upfront while maintaining the flexibility to compute results when required.

Sure, having access to everything at the grocery store sounds great. But buying it all upfront would waste your money (CPU) and overload your limited space (memory). With a personal shopper—Lazy Evaluation—you get exactly what you need, exactly when you need it, without wasting time, memory, or effort.

Now that we've gone over what lazy evaluations are, lets learn a bit about how they work!

How Do Lazy Evaluations Work Under the Hood?

At its core, lazy evaluation relies on the idea of delayed computations. Instead of immediately evaluating an expression or operation, lazy evaluation wraps the work in a placeholder, a function that will compute the result only when explicitly invoked.

These placeholders are often called thunks.

What is a Thunk?

A thunk is a function that delays the computation of a value. Instead of computing a result directly, you return a function that, when called, produces the result.

Here is how you could create a thunk in Clojure:

(defn expensive-computation []

(println "Running expensive computation...")

42)

(def my-thunk (fn [] (expensive-computation)))

(println "Computation delayed...")

(println "Result:" (my-thunk))

;; Output:

;; Computation delayed...

;; Running expensive computation...

;; Result: 42

Here’s what’s happening:

- The actual computation is wrapped inside a function (

my-thunk). - The computation doesn’t run until you explicitly invoke

my-thunk.

This is the foundation of lazy evaluation. Instead of calculating results immediately, Clojure (and other languages that support lazy evaluation) builds thunks to delay the work.

Lazy Sequences in Clojure

Clojure makes lazy evaluation seamless with its lazy-seq macro, which builds lazy sequences by creating thunks under

the hood.

Take a look at this infinite sequence of numbers:

(defn lazy-numbers [n]

(lazy-seq (cons n (lazy-numbers (inc n)))))

(take 5 (lazy-numbers 1))

;; => (1 2 3 4 5)

Here’s what happens step by step:

lazy-seqdelays the creation of the rest of the sequence. It wraps the computation((cons n (lazy-numbers (inc n))))in a thunk.consconstructs the sequence one value at a time.- When you call take, Clojure evaluates only as much of the sequence as necessary to satisfy the request.

Under the hood, Clojure generates a chain of thunks:

- lazy-numbers 1 → thunk for 1 and a delayed call to lazy-numbers 2.

- lazy-numbers 2 → thunk for 2 and a delayed call to lazy-numbers 3.

- And so on…

Each thunk is evaluated only when the next value is requested.

Memoization: Avoiding Repeated Computations

To make lazy evaluation efficient, Clojure memoizes the results of each thunk. Once an element of a lazy sequence is computed, Clojure ensures the thunk is replaced with the computed value. Subsequent accesses to the same element reuse the memoized value instead of re-executing the thunk.

(def lazy-nums

(lazy-seq

(println "Generating numbers...")

(cons 1 lazy-nums)))

(take 2 lazy-nums)

;; Output:

;; Generating numbers...

;; => (1 1)

(take 4 lazy-nums)

;; Output:

;; => (1 1 1 1)

What’s Happening?

- lazy-seq delays the creation of the rest of the sequence by wrapping the computation (cons 1 lazy-nums) in a thunk. This ensures that the computation is only performed when required.

- The first call to take triggers the computation for two elements. As the sequence is traversed, Clojure evaluates the thunk and computes the first value, which is cached.

- Subsequent calls to take reuse the cached value instead of recomputing it.

Why is this useful?

Lazy evaluation is incredibly powerful because it allows Clojure to handle complex operations in an efficient and resource-friendly way. For example, it makes it possible to work with infinite sequences without crashing, as values are generated only as needed instead of all at once. This deferred computation also enables Clojure to chain transformations like map, filter, and take seamlessly, processing only as much data as the program explicitly requires. Additionally, by avoiding unnecessary work, lazy evaluation saves memory and CPU cycles, ensuring that resources are used efficiently and computations are performed just in time.

Lazy evaluation puts you in control of when and how computations happen, ensuring your code is efficient, predictable, and resource-friendly.

Common Pitfalls

Lazy evaluation is incredibly powerful, but even the best tools have trade-offs. Like that personal shopper we talked about earlier, things can go wrong if you’re not careful. Maybe they pile up too many errands (thunks) at once, take too long to deliver what you need, or forget to stop when you’re out of space. Let’s look at some common pitfalls of lazy evaluation and how to avoid them.

1. Space Leaks: The Cart That Keeps Growing

Imagine your personal shopper keeps piling items into a cart without ever dropping them off. They’re holding onto things you don’t need anymore, and eventually, they run out of room. In programming terms, this happens when unevaluated thunks accumulate in memory.

Lazy sequences can accumulate unevaluated work (thunks), leading to memory issues when processing large datasets.

(defn sum-lazy [xs]

(reduce + (map inc xs)))

(sum-lazy (range 1e6)) ;; Potentially problematic

In this case:

mapcreates a lazy sequence of incremented values.reduceforces evaluation, but because map is lazy, it holds onto unevaluated thunks while traversing the list.- With a sequence as large as this, it can lead to high memory consumption.

To avoid space leaks, force strict evaluation with doall or dorun when you know you’ll need the entire sequence:

(defn sum-strict [xs]

(reduce + (doall (map inc xs)))) ;; Forces evaluation upfront

(sum-strict (range 1e6)) ;; Safe and efficient

2. Delayed Errors:

Now imagine your shopper delivers eggs, but halfway through, you realize they've gone rotten. Worse, you don’t find out until you’ve already started cooking. Lazy evaluation can delay errors, so bugs might only appear when computations are finally forced.

Errors in lazy computations may not appear until the sequence is actually used, making bugs harder to trace.

(def bad-seq

(map #(if (= % 3) (throw (Exception. "Bad number!")) %) (range)))

(take 5 bad-seq)

;; Output:

;; Exception: Bad number!

Here, the sequence seems fine until take forces evaluation. Debugging becomes tricky because the failure point is deferred.

To catch errors earlier, force evaluation of a small portion of the sequence during testing:

(doall (take 5 bad-seq)) ;; Forces evaluation, revealing the error early

3. Performance Overhead: Too Many Trips to the Store

Your shopper is efficient when you only need a few items, but if you ask for the entire store one item at a time, their back-and-forth trips add unnecessary overhead. Similarly, lazy evaluation introduces slight performance costs because of thunks and extra function calls.

;; Lazy sequence

(time (reduce + (filter even? (range 1e6))))

;; "Elapsed time: 125ms"

To fix this, you may want to consider doing all of your shopping up front if you know you'll need all of it.

;; Strict sequence using doall

(time (reduce + (doall (filter even? (range 1e6)))))

;; "Elapsed time: 90ms"

It is worth nothing that in cases where the dataset is incredibly large, it might be more practical to leave it unrealized and process it incrementally, such as in chunks or buffers to avoid issues with memory limitations.

4. Infinite Sequences Without Proper Control

Infinite sequences are one of the superpowers of lazy evaluation, but they can become a nightmare if your shopper doesn’t know when to stop. Asking for an infinite list of items without limits will leave them stuck in the store forever.

(def infinite-nums (iterate inc 1))

(reduce + infinite-nums) ;; Uh-oh, this runs forever!

Here, the program attempts to reduce an infinite sequence of numbers, leading to an infinite loop.

Always apply limiting functions like take or take-while when working with infinite sequences:

(reduce + (take 1000 infinite-nums)) ;; Safe and finite

Key Takeaway: Use Laziness Intentionally

Lazy evaluation is an incredibly powerful tool, but it comes with trade-offs that require careful consideration. To use it effectively, it’s important to be mindful of space leaks, which can occur when unevaluated thunks pile up in memory. In these cases, forcing evaluation with tools like doall can help prevent unnecessary memory usage.

Similarly, delayed errors can make debugging tricky, so it’s best to test small, isolated computations to catch issues early. When working with infinite sequences, always ensure proper control by applying limiting functions like take to avoid infinite loops or hanging programs.

Lastly, while lazy evaluation shines in many scenarios, it’s important to balance your performance needs. For smaller datasets or cases where all values will be processed, strict evaluation might be faster and more appropriate.

By understanding these pitfalls and applying lazy evaluation intentionally, you can write code that is clean, efficient, and predictable. With a thoughtful approach, you’ll take full advantage of laziness while avoiding its downsides.

Smart Laziness: The Secret to Doing Less and Achieving More

Lazy evaluation in Clojure is like having the ultimate grocery-shopping assistant. It fetches ingredients only when you need them, avoids unnecessary trips (wasted work), and keeps your kitchen spotless (efficient memory usage).

However, even the best assistant needs clear instructions. Watch out for memory leaks when unevaluated work piles up, delayed errors that appear too late, and performance overhead caused by too many back-and-forth trips.

Used intentionally, lazy evaluation empowers you to write programs that are cleaner, smarter, and more resource-efficient.

So next time you write code, ask yourself:

"Do I need this now, or can I let laziness do the work later?"

Stay intentional. Stay clean. Stay lazy.